Devalued Dreams

How the education system wastes our time, money, and talent.

Risk & Progress explores risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future for all. Subscriptions are free. Paid subscribers gain access to the full archive and Pathways of Progress.

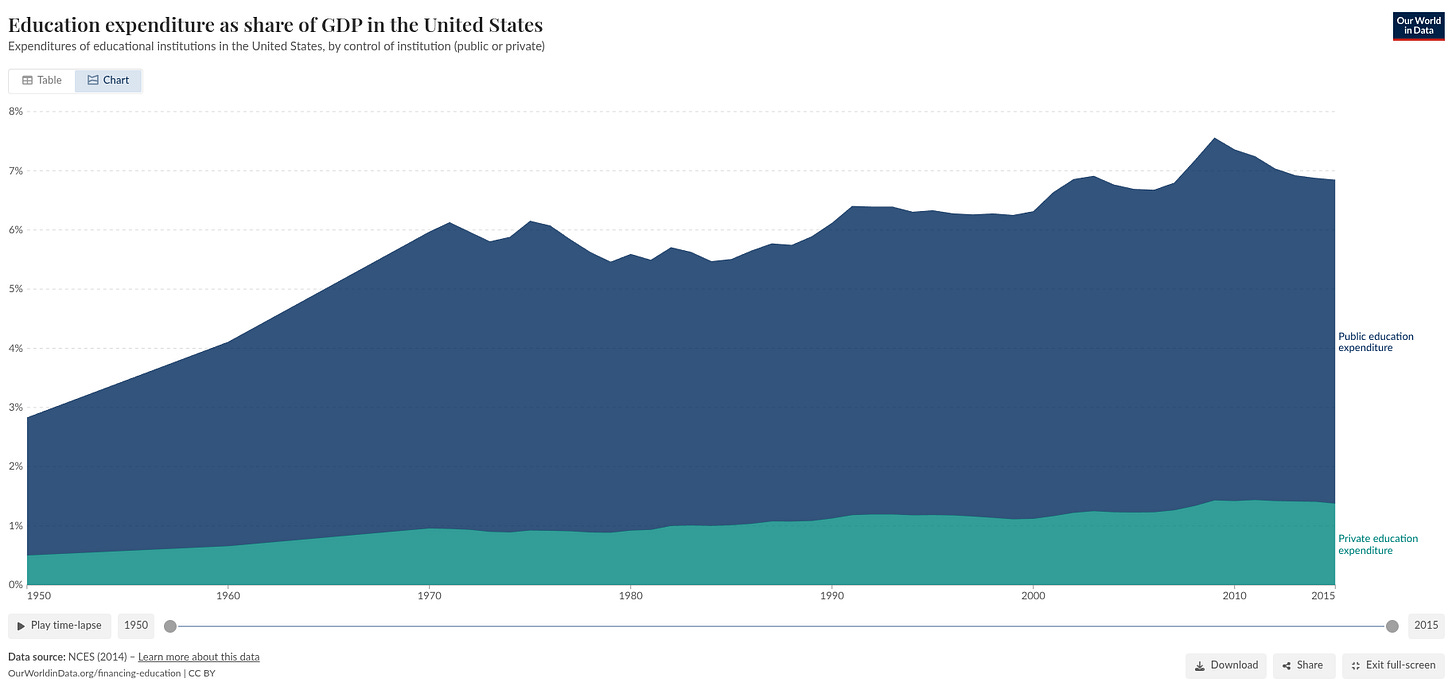

When it comes to human progress, the paramount importance of the discovery and dissemination of knowledge cannot be understated. It may not, then, appear befitting for me to attack the education system, which is seen as playing a crucial role in that process. Yet, there is a compelling case to be made that societies are misallocating their young’s time and money, forcing them to spend thousands of hours studying subjects they will never use and/or to take on loans to fund degrees that provide little tangible benefit. Indeed, despite spending almost $1 trillion annually on education, or about 6 percent of the US GDP, we still hand diplomas to high school and college graduates who fail basic literacy and math tests. Despite this, or perhaps because of this, the race to outshine each other with yet more diplomas and certificates continues.

“Human Capital”

In his book, The Case Against Education, author and economist Bryan Caplan notes that the standard justification for funding education is that it cultivates positive spillovers by expanding our “human capital.” This notion is as intuitive as it is attractive. As our society has become more complex and technology more advanced, we need to raise new generations of humans with the advanced skillsets required for this new age. As compelling as this argument might be, however, it seems little more than just another convenient myth we tell ourselves. There is strikingly thin evidence that the education system is actually an investment in our “human capital.”

To illustrate this problem, Caplan begins with a thought experiment. Imagine you are a “Martian sociologist” studying those industrious little humans on the Blue Planet. To better understand their society from afar, you devise a clever study to examine what humans teach their young in school. It’s only logical, after all, that economically scarce resources would be prudently spent preparing young humans for the real world. To an extent, the education system does exactly that. A considerable amount of time is spent teaching numeracy and literacy, universally beneficial subjects. However, considerably more time is allocated to other subjects, including teaching foreign languages, poetry, classical literature, and geometry. From this, as a clever Martian researcher, you might conclude that human society is filled with well-compensated poets, writers, translators, and that solving quadratic equations was part of a daily experience.

Of course, this is not the case. Much of what is taught in school is unused in adulthood. This education mismatch extends to the higher education system. Caplan notes that in 2008-09, over 94,000 graduates were bestowed a psychology degree. When we consider, however, that there are only 174,000 practicing psychologists in the entire country, and far fewer job openings, it’s clear that the vast majority of them will not find employment as a psychologist. Similarly, in just one year, over 83,000 students graduated with a degree in “communications,” far outnumbering the 54,000 people employed as reporters/news broadcasters, which again far outnumbers job openings in that field.

Yet, while we allocate significant resources to teaching students unnecessary material, we are falling short in our effort to educate them in universally essential subjects. Studies have found, for example, that a majority of Americans fail the very same citizenship exam they require of immigrants. These include basic questions like, “Is the Bill of Rights part of the Constitution?” and “What are the three branches of government?” Scientific illiteracy is equally bad; one in every four Americans doesn’t know that the Earth orbits the Sun, and about one in three doesn’t understand that atoms are larger than electrons.

Defenders of the education system counter that we shouldn’t judge the system’s merits on the mere retention of information; schools teach pupils how to ask the right questions, to “learn how to learn,” and how to apply these skills outside the classroom. Caplan writes, however, that the data does not support this notion either. At best, students learn what they were taught in school, but almost universally fail to apply their knowledge outside the classroom before forgetting much of what they had learned. I believe that we can attribute these low retention and application rates to schools routinely teaching subjects in isolation, without clarifying their relevance to real-world applications. This is difficult to do when the subject has no real-world relevance in the first place!