Pollution's Peak

The Environmental Kuznets Curve

Risk & Progress explores risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future for all. Subscriptions are free. Paid subscribers gain access to the full archive and Pathways of Progress.

We've examined how the "social supercomputer" has very nearly turned our world into a billionaire planet, driven by an unprecedented abundance of goods and services. It's tempting to assume that this flood of material plenty would ultimately ravage the planet, exhausting its resources and poisoning it in the greedy race to material wealth. In truth, though, the picture is far more complex. During the initial phases of prosperity and progress, people undeniably degraded the natural world, clearing vast woodlands, contaminating rivers and lakes, and polluting the skies. Yet as societies progressed, our ecological impact shifted, becoming progressively milder; demands for commodities dematerialized, woodlands reclaimed lost ground, and the pollution shrouding urban centers began to lift.

The Environmental Kuznets Curve

We have already discussed growing material abundance, as evidenced by collapsing time prices, which tells us that commodities and products are becoming more abundant relative to our total population. We did not, however, address the question material abundance of goods might impact the environment. Surely, a growing population that is also becoming wealthier is consuming more and more of the Earth’s resources, right? It follows that, eventually, the growing need for these resources would strip our Earth bare and leave environmental toxification and destruction in its wake.

As it turns out, maybe not. Paradoxically, as it relates to the environment, progress appears to be following a “Kuznets curve.” In the early stages of growth and progress, yes, we do consume, toxify, and pollute, but beyond a certain level of wealth (read knowledge), the opposite appears to happen. Our population and economies continue to grow, but total resource usage begins to fall, and our overall environmental “footprint” recedes. Even as the United States’ population and economy grew in the first two decades of the 21st Century, for example, Americans used less gold, copper, steel, aluminum, fertilizer, paper, etc. In fact, of the 72 resources tracked by the U.S. Geological Service, 66 of them are “post-peak,” meaning annual US consumption is falling. The same story is repeating itself in other wealthy countries as well; our need for commodities is rapidly evaporating.

The knowledge produced by markets, the social supercomputer, makes this possible, perhaps even inevitable, because pricing pressure is always looking for ways to do more with less. For example, when the first aluminum cans were introduced in the late 1950s, they required about 85 grams of aluminum metal each. Fifty years later, the same-sized can needed just 13 grams of metal. For a more tech-heavy example, think about this: a single lightweight fiber optic cable can carry many times more information than a heavier copper cable. Likewise, the smartphone engulfed many consumer goods into a single device; it “dematerialized” the alarm clock, scanner, calculator, pager, phone, camera, music player, calendar, books, radio, flashlight, sticky notes, a dictionary, a thesaurus, an address book, maps, and other products that would have been produced separately.

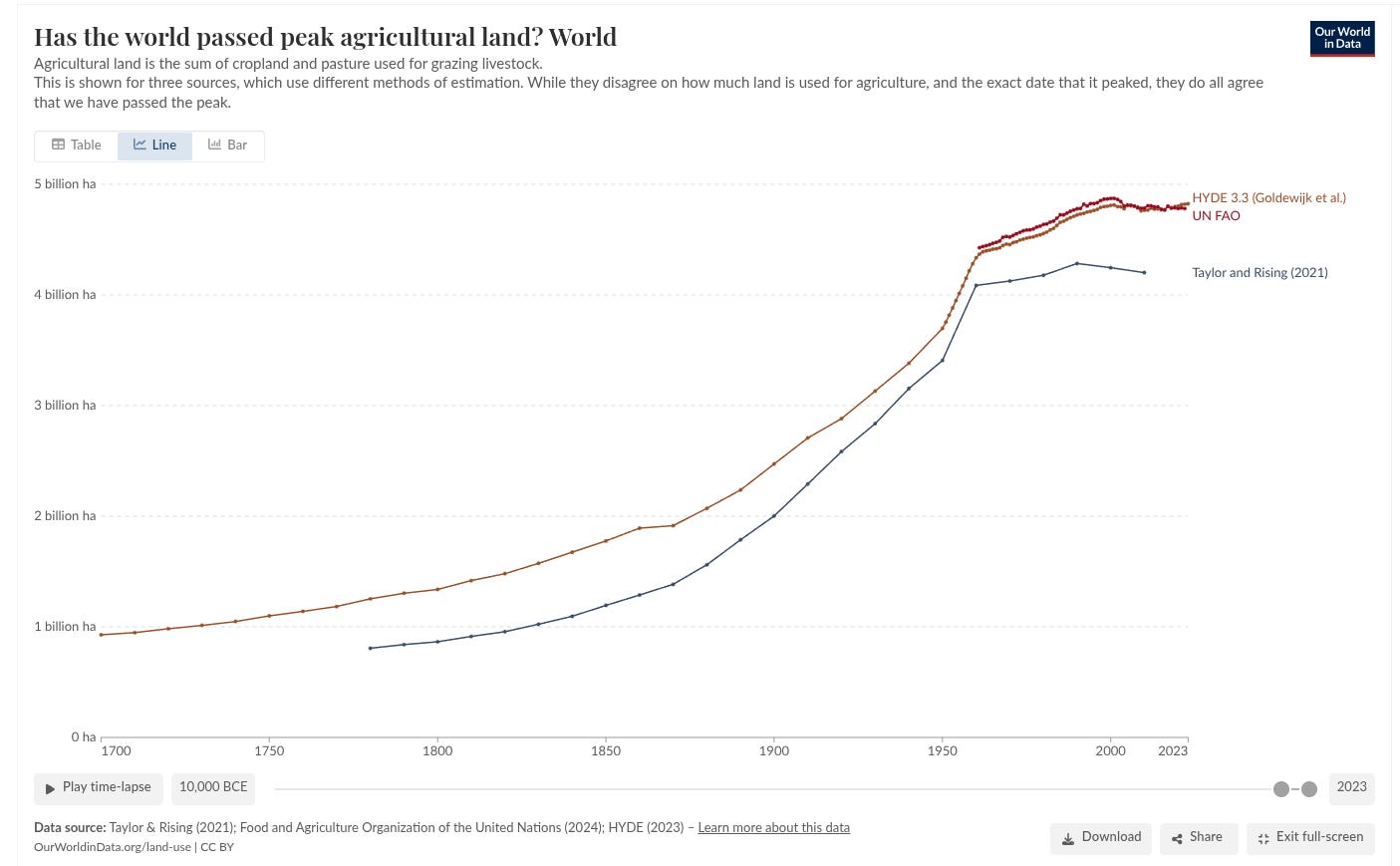

Return of the Forests

Even as our numbers grow, our demand for agricultural land is also diminishing. As we've explored, from the advent of the scratch plow to the development of dwarf wheat and rice varieties, humanity has continually innovated to extract more food from less land, while conserving water and fertilizer. Time and again, we've outtun Malthus, demonstrating that ingenuity can overcome even the direst resource constraints. Combined with decelerating population growth, these advances suggest that we've likely passed the peak of global agricultural land use—or are on the cusp of it. Though projections differ, the chart below illustrates that farmland dedicated to agriculture crested in the early 21st century. Absent major disruptions, we can anticipate a steady reduction in agricultural land requirements as we approach the 22nd century

With diminishing requirements for farmland, the planet's woodlands and grasslands are rebounding in some regions. Deforestation remains a prominent environmental issue, yet its tempo has notably slowed in modern times, even as worldwide economies have flourished. Per the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), deforestation has decelerated by around one-third since the 1990s. Net forest loss declined from 7.8 million hectares per year in the 90s to 5.2 million per year in the 2000s, and 4.7 million between 2010–2020. Note that we are still razing forests in much of the world; the deceleration in net forest loss comes from an offset. We are adding 5.5 million hectares of new forest cover every year.

Indeed, in about half of the world today, the dominant trend is afforestation or reforestation. Unsurprisingly, the regions where forests are returning include “wealthy” countries, such as those in North America and Europe, which now have more forest coverage than they did before the Industrial Revolution. Even rapidly developing nations, including China, Vietnam, and India, however, are also witnessing net forest growth. A study from the University of Helsinki found that between 1990 and 2015, annual forest coverage increased by 1.31 percent in high-income countries and by 0.5 percent in middle-income countries. Forest coverage, in fact, only decreased in low-income countries. The common denominator, once again, is material wealth and progress.

While we typically think of deforestation as a consequence of economic growth, it might be better thought of as a consequence of relative material poverty. Indeed, the wealth threshold for “turning the corner” on deforestation occurs around a GDP per capita of $4600. There are two mechanisms at play here. First, as countries develop and citizens are lifted out of abject poverty, public pressure can focus more on protecting the environment. Poor nations cannot afford to protect their forests as well as richer ones can. Second, we simply require less wood, paper, and land than we did in the past. Thus, the most direct, if counterintuitive, means of protecting the world’s forests is to accelerate global economic growth and ensure that all nations break through that threshold as quickly as possible.

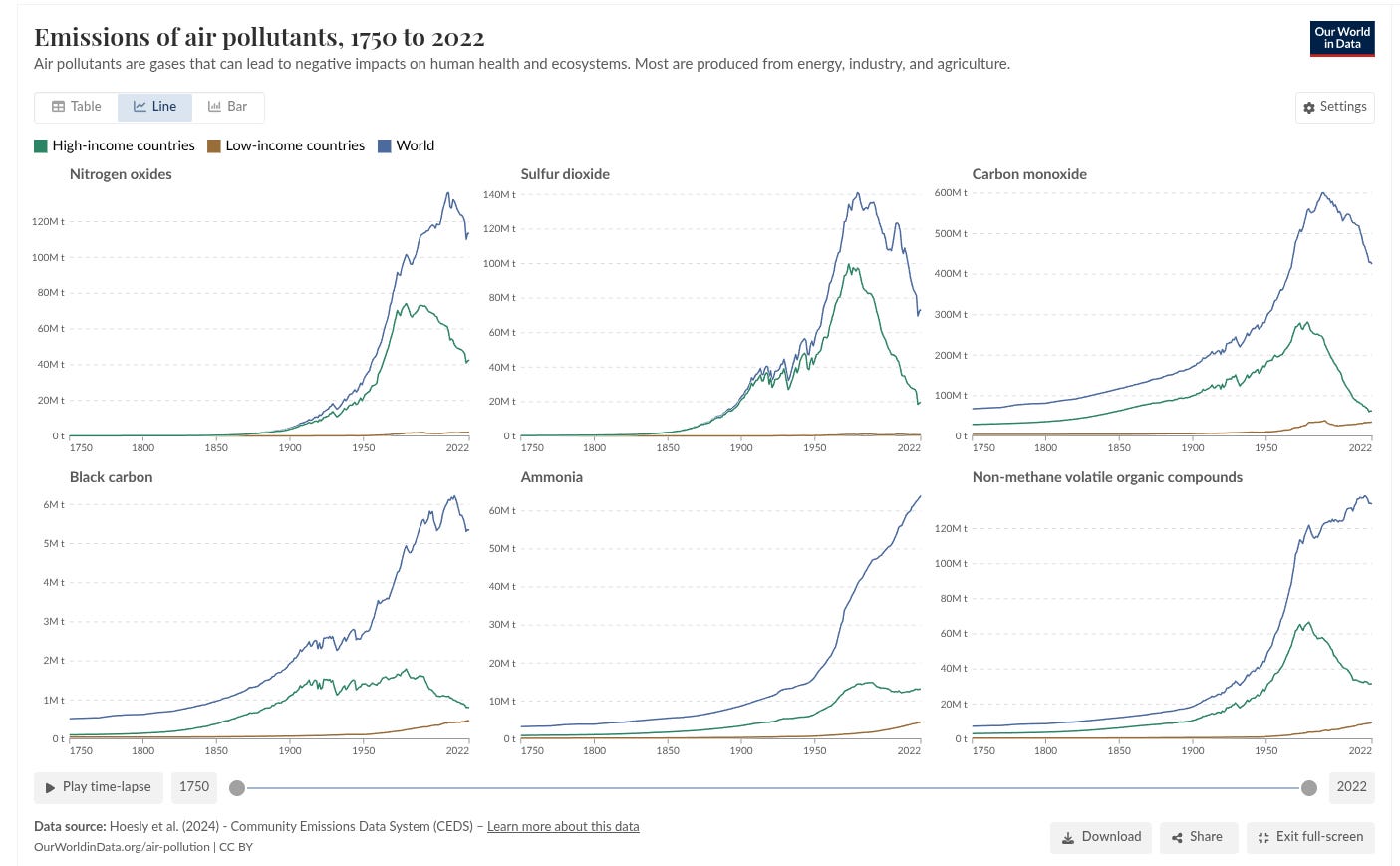

Clearing Skies

Wealth and progress not only restore our forests but also clear the air we breathe. The above graph from Our World in Data vividly demonstrates this by tracking emissions of major pollutants. In particular, these include nitrogen oxides (NOx), which foster smog and respiratory irritation; sulphur dioxide (SO2), the primary culprit behind acid rain; and black carbon (soot), a key driver of harmful particulates. The pattern is unmistakable—emissions spike in early industrialization phases, then plunge as countries amass wealth and as innovation progresses. Indeed, even as the population and global economy grow, the skies are clearing around the world.

At the same time, our growth is decarbonizing. We have passed through several energy revolutions, each less carbon-intensive than the last. As Steven Pinker notes, preindustrial societies relied on dry wood with a carbon-to-hydrogen ratio of about 10:1. Coal, which fueled the First Industrial Revolution, has a carbon-to-hydrogen ratio of roughly 2:1. At 1:2, petroleum drove the Second Industrial Revolution, and today natural gas leads with an even lower ratio of 1:4. Accordingly, the U.S. Energy Information Administration, reports that coal emits around 100 kilograms of CO2 Per Million BTU, while petroleum emits around 70kg, and natural gas, just 50kg. With each step up the energy ladder, carbon emissions dropped about 30 percent. The “social supercomputer” was decarbonizing and cutting pollution long before the terms “climate change” or “conservationism” entered the public lexicon.

Not only is carbon intensity falling, but some 32 wealthy countries are growing while also reducing their absolute CO2 emissions. This fact should be transformative for those concerned about climate change; we don’t need to choose between wealth and Earth. The environmental Kuznets curve lets us choose both. Meanwhile, developing countries are pivoting earlier; their economies grow with reduced pollution, carbon, and deforestation compared to those that industrialized earlier. This is further evidence that the “degrowth” agenda is fundamentally misplaced. Contrary to the headlines and the pundits, we are heading in the right direction. Stunting growth risks entrenching the status quo, preventing us from sliding back down the Kuznets curve. Once again, growth is not the disease; it is the cure.

Next in this series:

Previous:

This is such a crazy thing and it makes sense when you think about it but too few people pause to think about it. It's a good story and gives hope.

thanks for the interesting research, a positive approach while the common narrative is telling the opposit.

can you please correct the link for ourworldindata . thanks