The Gravity Telescope

From Galileo’s glass to gravity’s grand lens

Risk & Progress explores risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future for all. Subscriptions are free. Paid subscribers gain access to the full archive and Pathways of Progress.

Technological advancements enabled us to extend the reach of our senses far beyond their natural limits. Earlier, we examined how technology allowed us to observe and study the microscopic world, from cells to subatomic particles. Now, we will explore how many of these same optical innovations also made it possible for us to see deep into the heavens above and around us. These capabilities, to resolve the hidden worlds both small and distant, have allowed us to, figuratively, go “back in time,” to unlock the secrets of life’s many mysteries. Using technology, we have gained a clearer understanding of the beginning of life, the origin of the universe, and perhaps even some insight into its future.

Bending Light

Like many inventions, there is no clear answer as to who invented the first telescope that allowed us to study things that our eyes could not perceive. Many spectacle makers claimed to have built the first telescopes as far back as the late 1500s, but many trace the first telescope to a patent application filed in the Netherlands in 1608 by Hans Lippershey. The basic function of a telescope is rather simple. The human eye, our ‘‘lens” to the world, is small, collecting only just enough photons to see the brightest of stars in the sky. Telescopes can augment the human eye, using larger lenses or mirrors, collecting far more photons, and enabling us to see much fainter objects. Ceteris paribus, the larger the telescope’s light-collecting area, or “aperture,” the more capable it is.

Though he didn’t invent the telescope, it was Italian polymath Galileo Galilei, who, inspired by the “Dutch perspective glass,” unlocked its potential. Galileo replicated the Dutch device using a convex objective lens with a concave eyepiece. Initially, with just a 1.5 cm aperture, Galileo would eventually fashion lenses up to 4 cm in diameter that would magnify objects up to 30x. It was with these early telescopes that Galileo observed spots on the Sun, mountains on our Moon, rings around Saturn, and the moons orbiting Jupiter. Armed with only these crude devices, Galileo overturned thousands of years of teachings about the universe. It wasn’t long before Galileo’s contemporary, Johannes Kepler, further improved the telescope’s design by substituting a convex lens for the eyepiece. This allowed for a wider field of view and higher magnification, albeit flipping the image “upside down.”

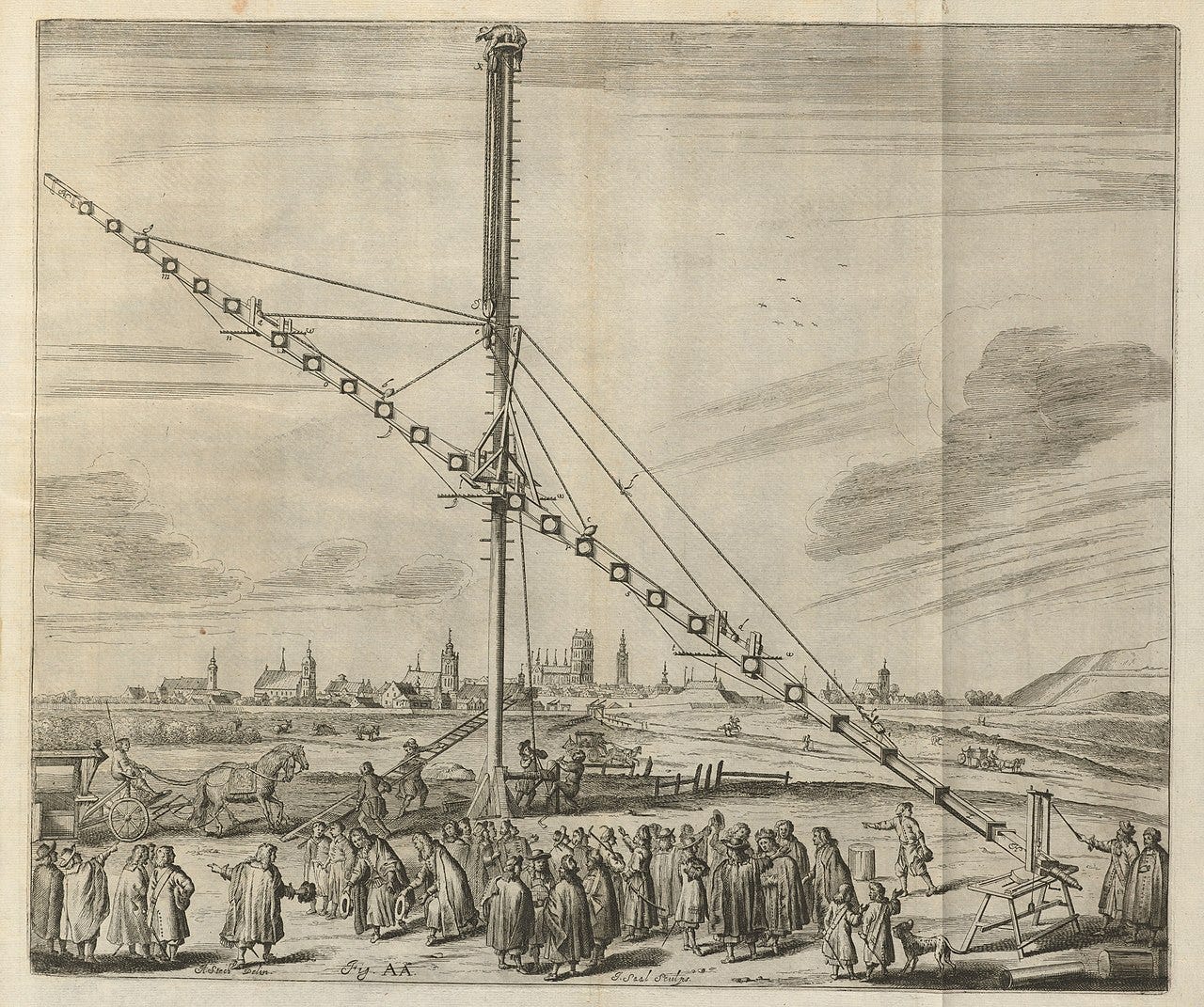

Subsequent astronomers would continue pushing the limits of telescope technology, but they ran into physical limitations. Early refracting telescopes used single-element objective lenses, meaning they had extremely high focal lengths. With every doubling of the aperture diameter, the focal length quadrupled, and, as a consequence, telescopes quickly grew unwieldy. By the end of the 17th century, the largest lenses were some 22 cm across, and telescopes grew so long that, in some cases, the objective lens had to be mounted on a tall pole or building with the eyepiece connected to it via a string.

A breakthrough came in 1733 when English barrister Chester Moore Hall developed the first achromatic lens. Using multiple peices of glass with different dispersions in the objective lens, he could reduce the chromatic aberration of the images produced while simultaneously reducing the focal length, allowing telescopes to shrink back to a reasonable length. However, limitations in lens-making technology restricted their size to about 10 cm. Thus, early refracting telescopes were either limited by the size of the lens or their unwieldy length. It would not be until the end of the 19th century that these limitations were overcome. In the meantime, an alternative telescope emerged: reflectors.

Reflecting Light

Just as the first refracting telescopes began scanning the heavens, thinkers began wondering if it was possible to use curved mirrors instead of lenses. The advantages were many; curved mirrors would not suffer the same chromatic or spherical aberration challenges, thus, they could be made larger and gather more light. The first functional reflecting telescope was built by Sir Isaac Newton in 1668. Though workable in concept, the speculum metal mirrors of the day (an alloy of mainly copper and tin) provided poor image quality. Nonetheless, new methods of manufacturing parabolic mirrors emerged in the 18th century, bringing about the first >1 meter telescopes, like William Herschel's “40-foot telescope,” which remained the largest telescope in the world for about half a century.

Reflecting telescopes, however, were burdensome to maintain. Primarily because the mirrors of the day didn’t last very long. Around 1858, a breakthrough in mirror technology emerged: silver-coated glass. Silver coatings were more reflective than speculum metal, their shine lasted longer, and the silver could be redeposited without remaking the entire mirror from scratch. Better, longer-lasting mirrors led to the construction of the first “modern” observatories, often located at high elevations to minimize light pollution and atmospheric distortions. Among these was the 100-inch (2.5-meter) Hooker Telescope, introduced in 1917. With this powerful device, Edwin Hubble proved that other galaxies existed outside of our own and that the universe had been, at one time, much smaller.

Silver mirrors still suffered challenges, however, as they had to be “resilvered” every few months. Then, in 1932, came another breakthrough: John Donavan Strong, a physicist at the California Institute of Technology, developed a technique of “silvering” mirrors with aluminum using thermal vacuum evaporation. The new aluminum coatings greatly extended the life of telescopic mirrors, allowing them to get larger and easier to maintain. In 1948, the 200-inch (5-meter) Hale reflector at Mount Palomar became the largest telescope in the world. Hale, alongside the BTA-6 telescope in the USSR, would be unsurpassed for decades.

Silicon Savior

For a time, it seemed that telescopes had reached their limit. Any larger and their mirrors would sag under their own immense weight, and atmospheric distortions would make it pointless to build larger anyway. Then came the microchip, our silicon savior. Using computers and sensors, we could build telescopes with larger mirrors by leveraging the power of “active optics.” First pioneered in the 1980s by the 3.58-meter New Technology Telescope or NTT, computers monitor the image coming from the telescope several times a minute, actively adjusting the shape of the mirror to correct for minor distortions. This enabled the use of thinner, lighter mirrors, and for the first time, telescopes could use multiple smaller mirrors rather than a single large one.

A similar technology conquered the other limitation: our atmosphere. Even at high altitudes, the imagery from large telescopes was becoming distorted by the movement of the air above us. In the 1990s, further advances in computer technology gave way to “adaptive optics.” In contrast to active optics, where a computer corrects the image a few times a minute, adaptive optics makes minute changes several hundred times per second, making it possible to correct for tiny atmospheric distortions in real-time. The first telescope to utilize this technology was the 10-meter Keck telescope in 1993, more than twice the diameter of the Hale telescope decades earlier!

This technology will allow us to build bigger and more capable telescopes. The Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), scheduled for completion in 2028, will have an aperture diameter nearly four times larger than Keck, at some 39.3 meters. The ELT will be able to gather 100 million times more light than the unaided human eye and resolve, for the first time, details about exoplanets orbiting other star systems. This telescope may even provide us with the capability to determine the presence of life on these planets and/or their suitability for human exploration and future colonization.

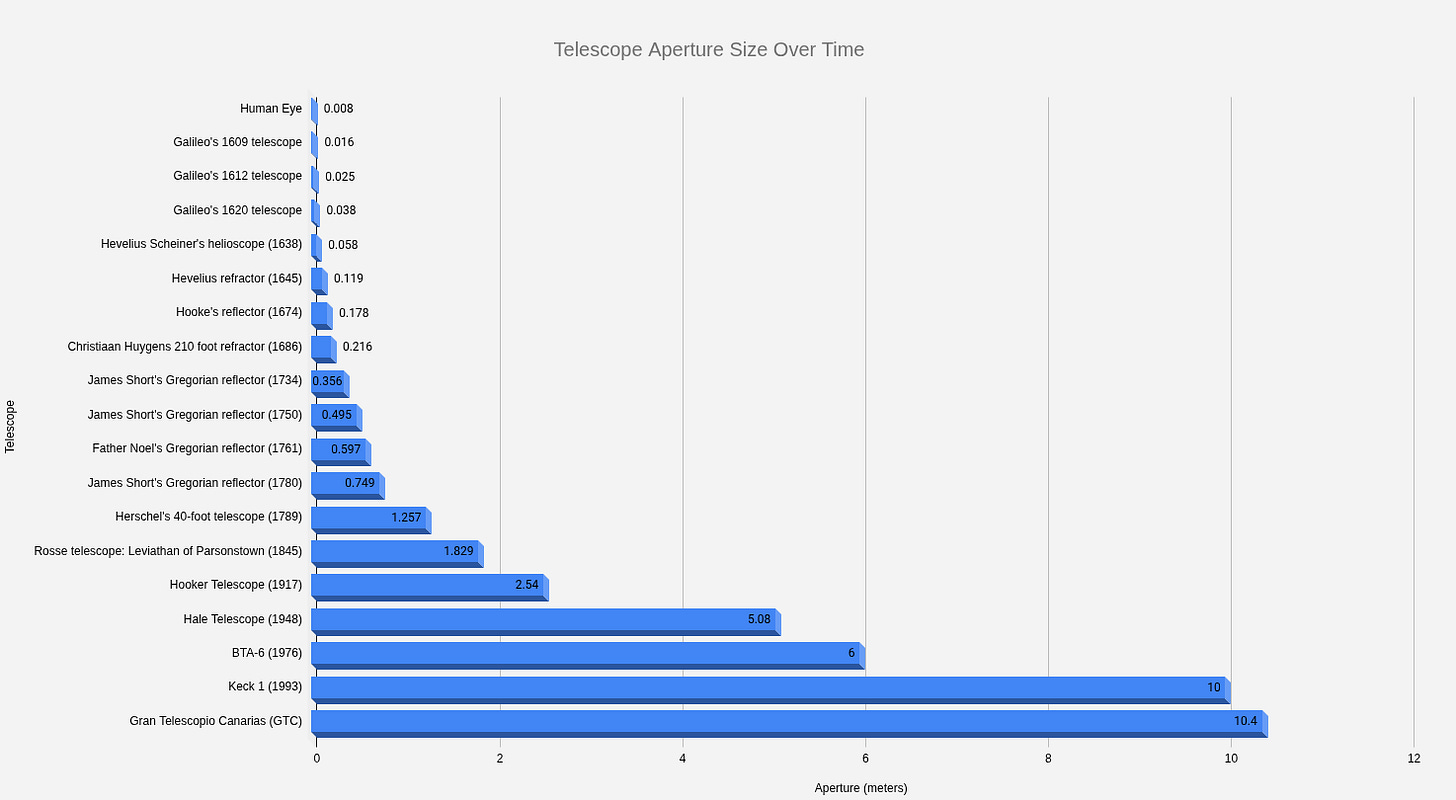

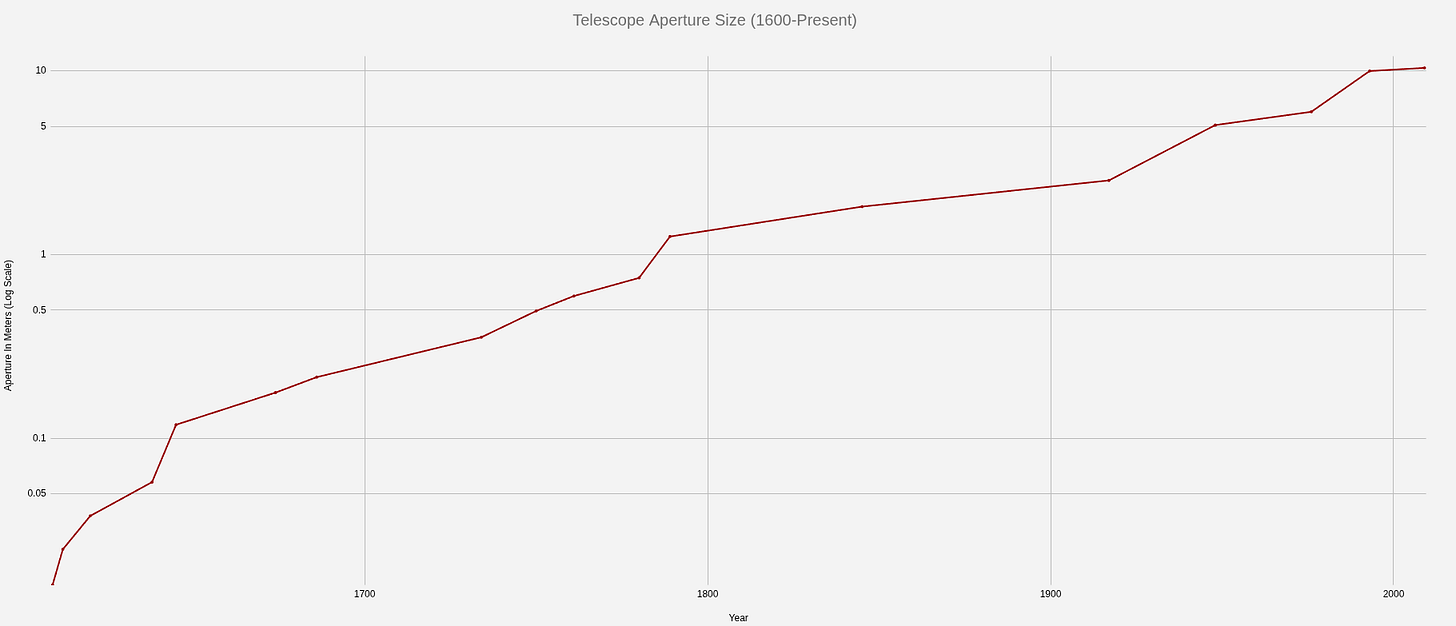

Above is a visual representation of the maximum aperture diameter humans have achieved over time. Plotted on a log scale (below), we can see an interesting and notable trend. Since 1650, aperture sizes have roughly doubled every 50 years. This sounds impressive, but actually undersells the improvement rate in total light collection. In these charts, I am only looking at the relative diameter of the aperture, but diameter is not the proper metric; the total area of the aperture is. With every doubling of the aperture diameter, we quadruple the total light collection area, meaning that our telescopes have become about 4x more capable every 50 years.

Space Telescopes

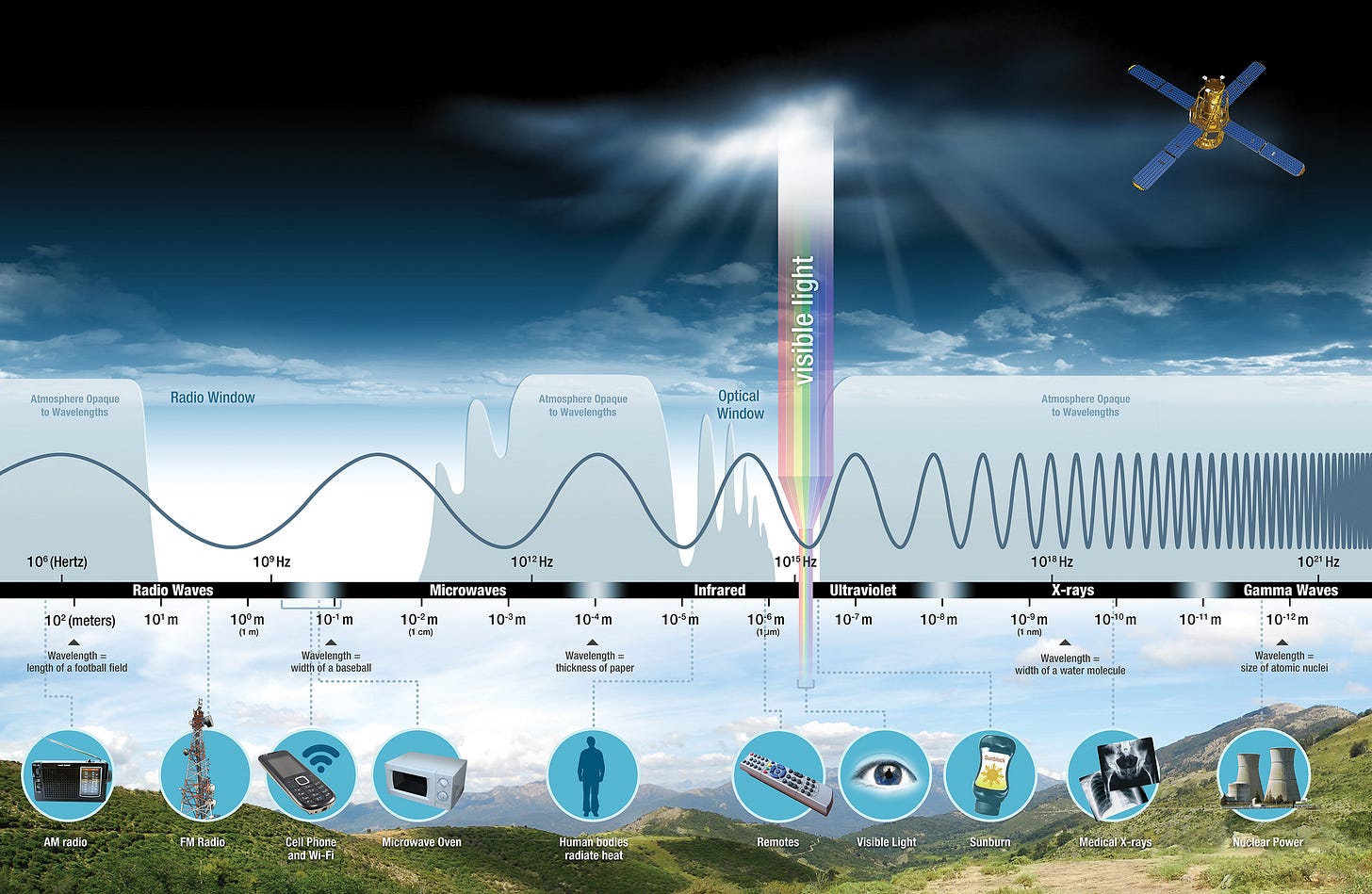

Ultimately, however, if our goal is to study the origins of the universe, even these massive Earth-based telescopes will hit a wall. First demonstrated by Edwin Hubble in 1929, the further an object is from us, the more “red” its color appears when we see it. This concept, known as “red shift,” is primarily caused by the expansion of the universe, which literally stretches light wavelengths toward the red color of the visible spectrum. To understand this, imagine drawing dots on a balloon that represent galaxies. As you inflate the balloon, representing the expansion of the universe, every dot moves away from every other dot, and the “space” between them stretches. Light waves that travel through this space get stretched too; their wavelengths get longer, and are shifted to red. The most distant objects get shifted out of the visible spectrum entirely into infrared light.

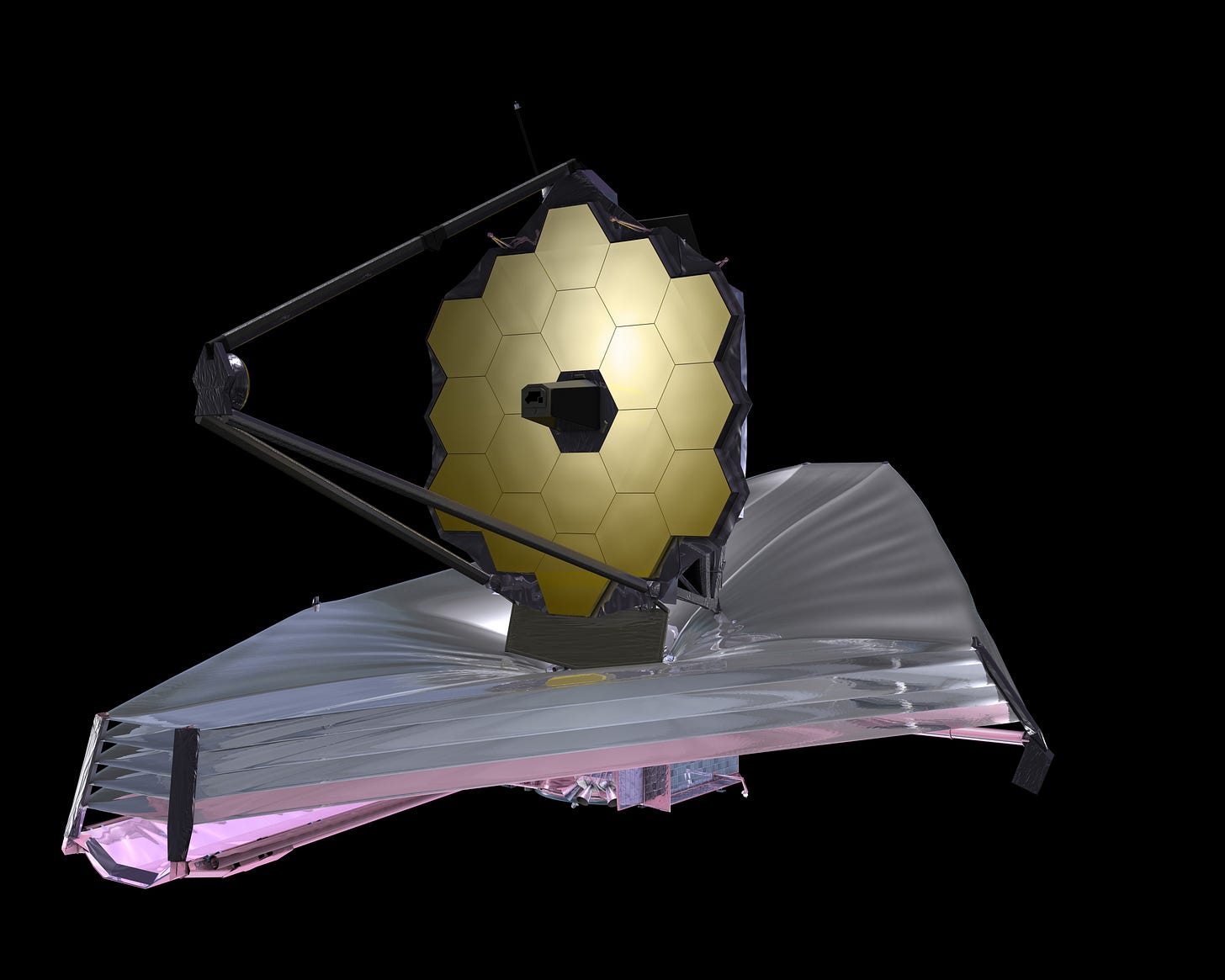

While we can build sensors that can pick up infrared light, there is a problem: the water vapor and CO₂ in Earth’s atmosphere absorb or block most infrared energy, and the thermal glow from our warm atmosphere adds noise that makes it difficult to “see” anything in this wavelength band. A space-based telescope, located outside our atmosphere, is therefore needed to see the most distant objects. The Hubble Space Telescope was among the first to experiment with near-infrared astronomy from space, but it was still located too close to Earth’s warm glow. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), on the other hand, was optimized for near- and mid-infrared observations. The JWST is located far from Earth, orbiting the Sun at the Earth-Sun L2 point, about 1.5 million km away. It’s equipped with a large sun-shield made of thin, reflective material that blocks heat from the Sun, Earth, and Moon and makes observations of very red-shifted objects possible.

The Gravity Telescope

Still, while the JWST will help us unlock the secrets of the early universe, it won’t be powerful enough to see and study many of the objects that we would like to know more about. It would be nice, for example, to be able to resolve, in detail, other planets orbiting other stars so that we could evaluate them for possible colonization prospects and, possibly, observe evidence of life on them. This capability, however, remains far beyond what can be achieved using existing lenses and mirrors. Enter the “gravity telescope,” or more precisely, the Solar Gravitational Lens (SGL) telescope, which might be considered the “Holy Grail” of telescope technology.

The SGL concept leverages the Sun’s immense gravity to act as a natural “lens”, magnifying and imaging distant exoplanets. As you recall, Albert Einstein correctly predicted that massive objects can bend light. Here, however, we focus those light paths, forming a giant cosmic telescope, using spacetime curvature to achieve unprecedented resolution. As light from a distant exoplanet grazes the Sun’s edge, it gets deflected by its gravity, converging at a focal region about 548 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun. That’s roughly 14 times farther than Pluto’s average orbit. This creates an “Einstein ring,” a circular distortion of the incoming light around the Sun’s position in the sky.

Spacecraft positioned in this region, equipped with a modest telescope and a coronagraph to block the Sun’s glare, could construct an image of a distant object from the deflected light. The space telescopes would scan the Einstein ring region, pixel by pixel, using computers to reconstruct the full high-resolution image from the data. With an SGL, light amplification could reach up to 100 billion times, allowing us to potentially map the surface features on exoplanets up to 100 light-years away with details as fine as 10 kilometers per pixel. With resolving power like this, we could even see features like large cities on the surface of these distant worlds. Remember, however, because of the distances involved, we would only witness what was, not what is. We would be seeing these planets as they appeared in their past, not as they appear today.

Alas, the gravity telescope is but a distant dream, for we would need to be able to send spacecraft further from the Sun than ever before, spacecraft that would need to act autonomously given the immense distances involved. Still, there is no reason the concept wouldn’t work. If we are daring enough, we could very well receive our first clear images of distant exoplanets before the conclusion of the 21st century. What we see on these alien worlds will forever change how we perceive the universe and our place in it.

You may also like….

I expect space telescopes to continue to tell us more about the galaxy. But the next big jump imo will be rotating ionic liquids and massive radio arrays on the dark (far) side of the moon. With these wide and unimpaired facilities, I expect we will see a new layer of detail.

I doubt I'll see a gravity lense telescope in anyone Alives life, but I would like to see a solar/fission sail craft sent out as soon as possible, and the sail could then be used as a reflector at the solar lensing point to give greater focus.

Yes, another very fine article.

On the gravity telescope collecting data pixel by pixel at 14 x the distance of Pluto from the sun, it looks like it would take about 77 hours (+/1 several more) for that data to transmitted to us once it has been locally collected, stored, and magnified electrically/electronically. I thought it would be much more than that, but I suppose that time span is not overly burdensome for the people who can put the telescope out there in the first place, taking perhaps decades to achieve?

One image that occurred to me was that whatever civilization might exist on one of those planets might also be able to build and send a 10 km square cube our way and block out any light from reaching us when it got close enough. This of course seems somewhat like the Borg, totally fanciful, but what us fearful and insecure humans might well dread.