Perfecting Patents

Reforming patents to work for, not against, innovation

Risk & Progress explores risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future for all. Subscriptions are free. Paid subscribers gain access to the full archive and Pathways of Progress.

The intellectual property system was created with good intentions, to light a fire under our inventors, to kindle the flame of experimentation and discovery. Yet, somehow, instead of a roaring flame, we have created little more than a damp blanket; better suited for snuffing out the flames than stoking them. We have previously explored the good, the bad, and the ugly of patents and intellectual property, as well as proposals to abolish and replace them with prizes. Unfortunately, this led to the uncomfortable and unfortunate conclusion that prizes were no panacea to our patent woes. Yet, not all is lost, for the path forward may lie in a hybrid system, one that treats patents as a kind of bounty. Here, I explore some of the many proposals for reforming patents so that they work for, rather than against, innovation.

Abolish Patents?

I won’t rehash the many challenges with patents, as you can read the full rundown here. I must reiterate, however, that patents can prevent the efficient diffusion and discovery of knowledge, especially when highly fragmented ownership results in the “Tragedy of the Anticommons.” As you recall, the Tragedy of the Commons occurs when shared ownership results in underinvestment and overuse of a resource. The Tragedy of the Anticommons, on the other hand, describes a circumstance where ownership is too divided, resulting in the underuse of a resource, in this case, an underuse of ideas. As one example, the airplane was an American invention, but a patent dispute between the Wright Brothers and Glen Curtis stymied progress stateside for years, allowing European nations to pull ahead after 1905. The US only began to catch up to Europe with the outbreak of World War 1 and only after the US government intervened in the dispute.

Some have suggested that the problems associated with patenting are so severe that we can, and should, abandon and abolish them entirely. There is some rationale supporting this notion, as well as some historical precedent to look to. During the height of World War 1, for example, the US Congress passed the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act. The Act allowed authorities to confiscate all German-owned US patents and make them available for compulsory licensing. Researchers studying the effects of the Act found that, counter to prevailing theory, compulsory licensing was associated with a ~20 percent increase in innovation by affected German and American firms. The researchers cautioned, however, that the scheme was a one-off wartime event; should compulsory licensing have remained law indefinitely, innovation likely would have been depressed.

In his book, Launching the Innovation Renaissance, Alexander Tabarrok noted that humans have been breeding and registering new types of roses for thousands of years. It was only after the 1930 Plant Patent Act, however, that breeders gained the ability to patent those breeds. The theory holds, therefore, that we should find a surge in new patented rose breeds after 1930. Yet we don’t. Over 80 percent of new breeds created thereafter remained unpatented. Roses are not unique in this regard either; indeed, most ideas of all shapes and varieties are not patent-protected, and innovation marches along just fine, if not better, without them.

This outcome is not universally true, however, as we saw earlier. There are specific industries where patent protection successfully stimulates innovation, most notably, the pharmaceutical industry. The Orphan Drug Act, for example, gave sponsors of drugs for rare diseases seven years of market exclusivity. The act led to a boom in the development of new lifesaving drugs for diseases that otherwise would not have been profitable to conquer. Patents have an outsized positive impact on the drug industry because of the high initial capital investment required to develop a new pharmaceutical product and the low marginal cost of production needed to mass-produce them.

Tabarrok concludes that one of the problems with IP law lies in the fact that, over time, we have become much more liberal in what is allowed to be patented. In times past, a tangible product had to be successfully demonstrated before a patent could be granted. Today, on the other hand, an intangible idea alone will suffice, and these ideas can be frustratingly broad. He points to the infamous “E-data” patent, granted in 1983, which covered everything from downloading photos, music, and other files. Creators were forced to pay royalties to E-Data for what was essentially a vague idea, not a technology in any reasonable sense. Tabarrok writes, “Edison famously said, ‘Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration.’ A patent system should reward the 99 percent perspiration, not the 1 percent inspiration.”

Instead of wholesale abolition, Tabarrok recommends splitting patents into terms of varying lengths based on the amount of “sunk costs” invested in them. An idea or innovation with low sunk costs would only be eligible to receive a short-term patent, perhaps two years. Long-term patents of 10 or 20 years, however, would be subject to higher scrutiny, requiring evidence to prove that the innovator expended a great amount of resources to develop the idea. Arguably, this solves many of the problems plaguing the current patent regime by shortening the duration of most patents issued. It does not, however, solve the deadweight loss and allocative efficiency challenges associated with long-term patents.

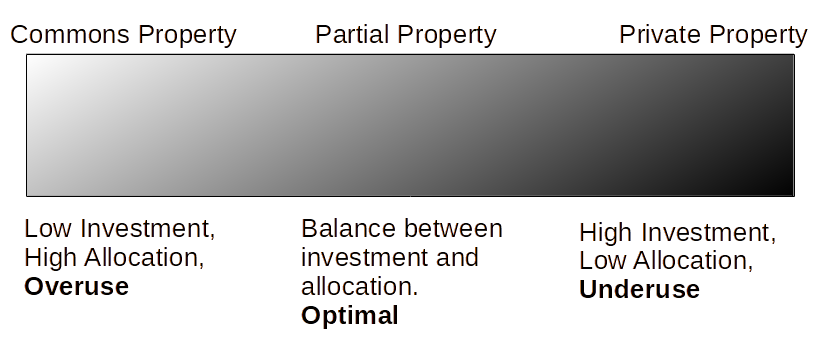

Recall that I previously argued that there is a “spectrum” of optimal property rights. Common ownership results in high allocative efficiency but low investment incentives. When ownership rights are too strong, however, investment incentives are high but allocative efficiency is low, resulting in property that is not used efficiently. At both extremes, whether public or private, the outcome is not fully optimal. The best property, I concluded, may not be commonly owned or privately owned, but rather a hybrid of both. For intellectual property, especially, we can use the existence of this continuum to our advantage.

Patents as Probabilities

To that end, Ian Ayres and Paul Klemperer propose a radical rethink of IP along these lines: Probabilistic Patents. They argue that an efficient patent policy should provide “constrained,” not absolute, market power. That is, the government should allow a limited amount of patent infringement to balance returns to inventors with social costs. One means of achieving this is to combine uncertainty with a delay in IP enforcement: to allow patent infringement some of the time. Probabilistic determination means that some “infringers” will calculate that the risk of potentially being found in violation of a patent is worth the potential profit. A few “infringers” will enter the marketplace, curtailing the monopoly power of the patent holder. Only a limited number of players would step in, however, because the market would naturally reach a point where the risk of “infringement” would outweigh the potential reward. Competition, therefore, would not wipe out the patentholder’s profits or nullify the incentive to innovate.

Notably, Ayres and Klemperer illustrate how a small amount of uncertainty dramatically reduces deadweight loss, the social costs of patents. For example, they calculate that if the probability of patent enforcement is cut to 95%, the market price of the patent falls by 10%, and the social deadweight loss is reduced by over 18%. This does marginally reduce the incentive to innovate, but we can compensate for this by lengthening the term of the patent. For example, reducing the probability of enforcement to 90 percent would require lengthening the patent term by just 3.4 years to achieve the same profits for the patent holder, while reducing the social cost of the patent by roughly 30 percent. In short, the researchers posit that society benefits from oligopolistic pricing for a longer period than it does under monopoly pricing for a shorter period.

A similar outcome could be achieved, however, through a Duopoly Patent Auction, where a patent grant would confer not only the right to an idea but also a mandate to auction it off to a second owner. As the “partial” patent owner, the inventor would still be able to profit from their idea and would also receive a hefty lump sum license payment from the second buyer at the patent auction. Consumers would benefit from access to lower-cost duopoly-priced ideas rather than monopoly-priced ones. This option seems a lot cleaner than rolling the dice with patent enforcement. Still, I find these proposals to be nonstarters. They may work in theory, but in practice, they would encounter all manner of human emotion and manipulation that could render them wholly counterproductive.

A Continuum of Excludability

We won’t need to roll the dice on patent enforcement, however, if we know its approximate value, and can make the patent market liquid and tradeable. Yet, determining the value of an is difficult because there is natural variation in an idea’s “degree of excludability.” In a study of this concept, Amy Kapczynski & Talha Syed note that 30,000 people die every year in ICUs from infections resulting from central-line catheters. The IP system, of course, would reward a company handsomely for developing a new antibiotic that saves these lives. But the solution doesn't need to be a new drug. In fact, the New England Journal of Medicine developed a life-saving innovation that cuts these infections by two-thirds: a simple checklist of standard hygienic and communication practices that can be performed at virtually no cost. A patent system would protect and reward the creation of a new drug, but it would struggle to reward the developer of this checklist.

Both inventions have similar social value, but one has greater market value. The reason is the natural degree of excludability. Even if one could patent the checklist, it would be impossible to monitor the activity of every ICU to ensure that royalties were paid when the system was used. A drug, on the other hand, is highly excludable; the legal system can prevent copies from being produced and sold on the market. Thus, when we discuss the market value of a patent or idea, that value is derived from the social value moderated by the fraction of that value that is excludable. We might think of an idea’s value as roughly following the formula below: the market value (V) is the social value (S) moderated by the fraction that is excludable (C).

V=C(S)

Patent Buyout Auctions

Of course, the best way to divine an idea’s value is to auction it in the marketplace. Patent buyout auctions were proposed in 1997 by Michael Kremer. In his proposal, an auction is used to determine the value of a patent, whereafter the government buys the idea and places it in the public domain. The concept of the sovereign buying and “open sourcing” a patent has historical precedent. Daguerreotype photography, invented in 1837, was the first means of taking photographs. The government of France recognized the innovation’s importance, purchased the patent, and placed it in the public domain. Free to use, the technology rapidly spread across Europe, and within months, the process of taking photographs was translated into dozens of languages. Chemists all across Europe quickly improved upon the technology, faster than they would have had the process remained patent-protected.

Kremer proposed that when a patent is filed and approved, it would automatically be subject to a public auction. The auction would be a Sealed Bid Second-Price Auction (SBSPA), where bids are submitted in written form without knowing the other bids in the auction. The highest bidder wins, but only pays the second-highest bidder’s price. This keeps bidders from trying to guess the other parties’ offers and focuses them instead on the patents’ intrinsic value. The government would also submit a bid, taking the private value of the patent (determined by the auction) and adding a multiplier of 2x. Why do this? Kremer argues that because ideas create positive spillovers that cannot be fully captured privately, we can enhance innovation by adding that compensatory multiplier. By default, of course, the government’s bid would win the auction, and the patent would immediately be placed into the public domain for the benefit of humankind.

The beauty of patent buyouts is that inventors are rewarded for their work, while society also immediately enjoys the fruits of new ideas. In my view, however, Kremer’s system is very vulnerable to manipulation. Since the government is buying the vast majority of patents at a significant markup, there is the risk that bidders and inventors will collude, driving up patent valuations and forcing the government to pay excessive prices. Kremer recognizes this and suggests that the government step aside on random auctions, creating risk for colluders. Even with safeguards, however, it is too easy for three CEOs to meet on a golf course and arrange a “patent pumping” scheme that would net billions in profit, even if they would take occasional losses. Additionally, I do not think this system would be affordable, as it would require trillions of dollars of spending every year.

Enter Harberger

If we step back, we can see that Kremer’s overarching goal was to determine the value of an idea so that we can reward innovators but also eliminate their monopoly power, which gives rise to the “Tragedy of the Anticommons.” We don’t necessarily need buyouts and auctions to do this, however. Once we understand that patent monopoly protection is a creation of the sovereign state, we can reframe patents as partially publicly owned. The owner has the right to profit from his idea, but must pay a portion to the sovereign authority that made this possible. A small annual tax, almost akin to a “lease” from the state, can transform patents from a monopoly into partially publicly owned property. As before, the challenge lies in accurately assessing the value of an idea, and that is where Harberger taxes come in.

To determine the value of an idea, we turn to the IP owners themselves. They self-assess the value, and the government charges an annual tax (ranging from 2 to 7 percent) based on that valuation. Naturally, IP owners will want to assess the value low to reduce their tax burden. This is why, under a Harberger system, anyone can buy IP at the self-assessed value at any time. For example, a patent holder might want to value their idea at $10 billion to prevent anyone from buying it, but with a 2.5 percent annual tax, they would have to pay $250 million a year to maintain their monopoly rights. Instead, they will rationally choose a realistic $100 million valuation, incurring a reasonable $250 thousand annual levy that is worth paying for patent protection. The combined constraints of the buyout price, which places a floor on the idea’s value, and the recurring tax, which forms a ceiling on that value, force a broadly honest self-assessment.

As we saw with probabilistic patents, a small tax would have a relatively large positive impact on the social costs of patenting. A tax of just 2.5% percent on property would significantly improve social welfare by optimizing the balancing of IP’s allocative and investment efficiency. For the first time, a patent or an idea can be purchased at a fair value without the “holdout problem.” At the same time, the tax is not so high that it would deter future innovation. This would be especially true if we combined the patent levy with lengthened patent terms, as Ayres and Klemperer suggest.

Perfecting Patents

Based on the above, I propose a new IP paradigm that builds on centuries of data and experience. As an initial action, there are two basic approaches. 1) We could split the existing patent system into two. Most ideas would still be patentable, but patent terms would be limited to two years. Think of this as a small extension to the “first mover” advantage. Long-term patents would remain available; however, they would be subject to far greater scrutiny and much harder to obtain. 2) In the alternative, we could abolish those short-term patents too, leaving only our extremely stringent long-term patents. Either way, we dramatically narrow the scope of what receives true, long-term patent protection.

What kinds of ideas should be granted long-term patents? The existing system already has two broad parameters. First, the idea must be new or “novel.” Second, it must be “non-obvious.” Yet, as we have seen, that analysis is subjective, and many patents have been granted to fairly “obvious” concepts. Perhaps, as Tabarrok suggests, we should demand proof of “sunk costs” to demonstrate the “non-obvious” nature of an idea. Additionally, as we have seen, many of the problems with patents arise out of poorly-defined boundaries. So, as a third parameter, I suggest that patents be granted only to ideas where the boundaries can be clearly defined. Primarily, this would limit patents to the chemical industry, including pharmaceuticals, which happens to be the only sector where patents seem to work anyway.

Upon receiving a long-term patent, the patentee will be required to self-assess its value and pay an annual Harberger levy upon that value. At that moment, also opens for purchase by a third party. IP owners will have the right to refuse any sale; however, every bid they refuse becomes the new assessed value upon which the Harberger levy is based. IP owners can stop paying the tax at any time. All they need to do is place the idea into the public domain for all to use. Here, I diverge from Kremer patent buyouts in a few ways. First, because we use Harberger taxation to make the IP market liquid, we no longer need the government to buy and open-source every idea. The state may purchase IP it deems worthy of the public domain, but this is optional.

Furthermore, if and when the government does this, I am not advocating that the state pay a 2x markup, as Kremer advocated. As noted in Stanford Lawyers magazine, we do not permit the full internalization of social benefits in any other property realm; thus, it is disingenuous to place such a demand on IP. If I plant flowers on my lawn, existing property law does not permit me to hunt down every passerby and charge them for the beautification I provided. The market need not provide a perfect capture of social benefits for inventors, only enough to cover the fixed and marginal costs of producing IP.

Thus, lacking mandatory government buyouts and extreme markups, my system is cheap to implement and immune to manipulation. Additionally, because IP would be subject to a small tax, it would not be rational for “orphaned” works to exist; most would be immediately released into the public domain. Similarly, the recurring tax on IP would discourage patent trolls as they would now face losses for squatting on unproductive IP. Furthermore, the system would greatly reduce the cost of IP litigation, for, in infringement cases, courts’ roles would be limited to adjudicating whether or not an infringement took place, freed from the arbitrary task of determining the damages suffered; this number would be publicly available.

The result is a narrow patent system that rewards innovators for truly novel, non-obvious, and clearly-definable ideas. Further, by slightly curtailing the monopoly power of the patentee, the system prevents the “tragedy of the anticommons” and the underuse of those ideas, ensuring efficient knowledge dissemination and follow-on innovation. All the while, we decimate the incentive system that feeds patent trolls and undermine the innovators themselves. We may never find a “perfect” solution to the patent problem, to accelerate and sustain our innovative spirit, but the system I have proposed, at the very least, gets us closer.

You also may like…

This is really interesting. Your proposal makes a lot of sense to me for intellectual property, and I wonder what we could learn for real property. Self-assessment of taxes with mandatory buyout could solve a major problem of land speculation. But there are so many second order effects, and the key difference that real property is rivalrous.

Thanks for the food for thought!

You must be an economist, no one else could be so foolish in that characteristic style.

If you want to suppress innovation, just make it a negative profit expectation for filing a patent, impose an up-front penalty equivalent to a DUI, make it cost a million dollars or more for each enforcement case, all of which is the case today, and only fools will file for patents, all the smart inventors will keep their ideas to themselves and the smart companies will keep trade secrets instead of patenting (which means publishing) their IP.

Correcting some of your false premises:

There is no profit for inventors now. There is no career path. There are virtually no serial inventors making a living, it's a less realistic ambition than movie star, bestselling novelist, or even multi-billionaire. Patents are already taxed, there are maintenance and renewal fees. There is effectively no market for patents, only sporadic deals in which 99%+ of the time the lawyers make more than the inventor. Virtually all patents are stolen from the inventors by universities and corporations who pay nothing to the inventor; they make accepting such theft a condition of employment or even of being allowed to pay tuition.

See my short essay: https://enonh.substack.com/p/nobody-wants-geniuses

(free $100T+ value idea at the end!)